Sustainable Software

Ok, so the title is Software Engineer or Software Developer, but writing code and building software is only part of the solution. The other half (or more) of the job is designing software solutions for humans to interact with. Software only is useful because we humans use it. Without us, the software is just some meaningless electricity in some far away warehouse. UI/UX design is important, but just as critical is developer operations (dev ops).

- Dev Ops

- outlines a software development process and an organizational culture shift that speeds the delivery of higher quality software by automating and integrating the efforts of development and IT operations teams – two groups that traditionally practiced separately from each other, or in silos.1

What as Dev Ops?

Don’t get me wrong, large scale production deployments can have very complex dev ops! However, even for a single developer, the tools and systems required are very easy, often free, and can massively improve productivity.

Here is my list of main dev ops goals. Some may seem obvious, but all of these are drawn from experience starting new projects as well as inheriting many projects of dubious quality.

- Source Version Mangement

- Rule 1: software changes need to be easily assigned, tracked, and checked

- Rule 2: environment variables need to be stored safely (important enough to state again)

- Deployments

- Rule 1: deploying new versions should be automated via CI/CD and require no human intervention

- Rule 2: staging site to test versions before production deployment

- Onboarding

- Rule 1: new devs need to be able to download and deploy system within a day2

- Rule 2: new devs should not be able to break production

The Fallacy of Saving Time

Dev Ops takes time to setup, but it is absolutely worth it. Here’s a story from my days as a contractor. At one company, it took 2 developers at least 4 hours each to deploy our application (at a generous minimum). Here’s how that math works out over just a single year:

That’s over a month of dev hours lost per year! Does any dev want to waste a month every single year running the same deployments? However, this is just the tip of the iceberg. If your system takes a day to patch, what happens when a major exploit is found in production?

This is a single example of poor dev ops, but time is money and similar math applies to dozens of scenarios.

So Let’s Do It Right

i. Source Version Mangement (svm/git)

Talking to my college friends, it seems a lot of CS majors do not learn Source Version Management (or SVM). Basically, we want a history of all of our code changes, and the ability to go back to specific checkpoints and fix things that break. There are a few tools for this, but I use git as the SVM and github.com to hold my repositories (as well as provide other dev ops tools, discussed later).

git is very powerful and very complex, but we only need a few commands to set up a useable CI/CD environment. This graph is a simple version of “git flow”, or a semi-standard way to use github branches.

gitGraph

commit

branch develop

checkout develop

branch featureName

checkout featureName

commit

commit

checkout develop

branch fixBug

checkout fixBug

commit

checkout develop

merge featureName

checkout main

merge develop

checkout develop

merge fixBug

checkout main

merge develop

main (previously defaulted to master): this is our production code. Never work directly from main. Never interact with main via CLI.

development: this is our staging code. This is where we start new branches

<namedBranch>: these are self contained changes to the project. Here we have featureName and fixBug, but often there are different categories of named branches such as feature/featureName or bug/bugName.

This is how we would setup a repository to follow basic git flow.

git config --global init.defaultBranch "main" # By default, git may still use `master`, so we set default to `main`.

cd projectFolder

git init

git push -u origin main # here we setup the remote copy of our repo

git checkout -b development # -b is only needed when creating a branch

git push

git checkout -b featureName

Now, we can work on featureName without impacting anything else. Additionally, other devs on our team can branch from development and any merge conflicts will be dealt with on the development branch before merging into main.

Once our feature is added:

git add . # the '.' convention will add ALL modified files. Only modify files that you need to. git restore fileName will undo any changes.

git commit -m "Added feature" # -m only allows inline commit messages. A commit is basically a checkpoint we can go back to later.

git push

git checkout develop

Now, we could immediately create a pull request from development into production, but it is preferable to have a staging or development site. A staging site is a live site that usually only devs/testers can access. So let’s deploy a staging site!

ii. Continuous Integration and Continuous Deployment (CI/CD)

My website is made with Hugo, a static site generator written in Go. It has a theme called Puppet, and I have it deployed to a custom domain (ivylikethevine.com) Originally I had used Github Pages alongside Jekyll, but found that the setup for a staging & production environment was tedious.3

Eventually, I switched to Cloudflare Pages, which I recommend as it allows us to access Cloudflare Zero Trust, a system to authenticate users before accessing webpages.4 Cloudflare Pages also defaults to creating preview pages, essentially staging sites per branch, and we can configure our staging site to deploy from the development branch when a change is pushed.

Luckily, Cloudflare has a pretty slick Github integration, so we can follow the instructions here. Note: only allow the minimum required permissions for a service integration. Cloudflare Integration should only have access to the repository(ies) that are deployed to Cloudflare Pages.

Custom Domains & DNS Pains

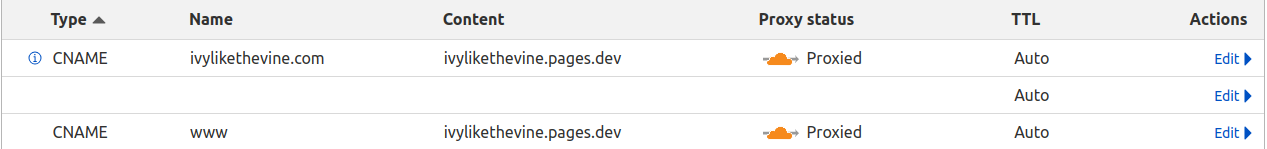

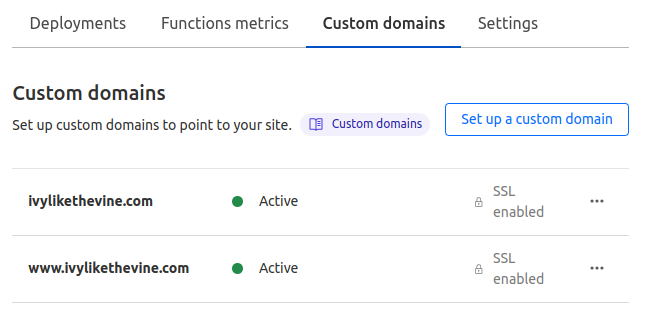

Github & Cloudflare pages host websites, but they do so using their own domains. Github uses a .github.io extension and Cloudflare uses a .pages.dev extension. We would obviously prefer our own custom domain, so what we have to do is change the DNS records for our site to point to the content deployed by our hosting platform. In Cloudflare, here is what my DNS settings look like for my website.

Our CNAME allow us to load the content of the pages.dev, but access it via our custom domain name. My domain name servers are with Cloudflare, which makes the setup very easy. If moving from Github Pages, make sure to remove the custom domain from the Github Pages site & to transfer name servers. We also redirect the www subdomain since it is still sometimes used, and we just want it to redirect to the same content anyways. We can also see that on our Workers/Pages configuration we have setup our custom domains.

Staging Environment

Now, we have automatic deployments from our main branch, as well as automatic preview branches! We could be done, but I prefer to just have one staging site, at least for now. In future, I will cover using Cloudflare Zero Trust to password protect all staging sites.

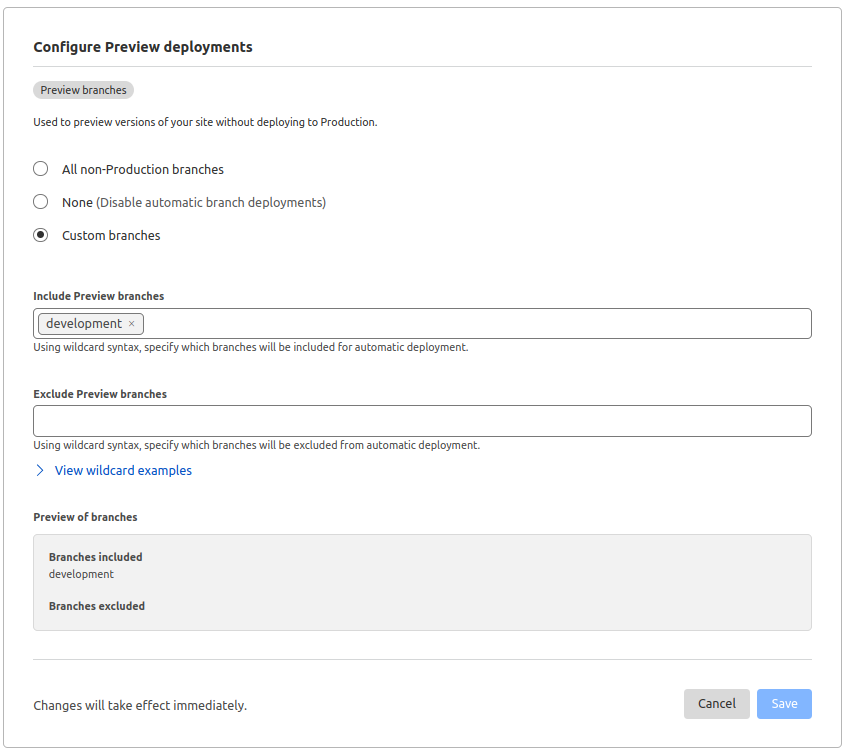

On the ‘Workers & Pages’ tab of Cloudflare, we can click on the details for our site, then head to “Settings”, then “Builds & deployments”. We can leave the top production branch alone, but here is my configuration for the preview deployments:

So now we only publish a live version of our development branch at https://development.repoName.pages.dev!

Two Environments, both alike in config

Having two environments now means we need to have configurations for each. Hugo allows multiple configs, and we only need two:

config/_default/config.tomlfor development & staging- This config has 90% of the site settings, since we need most of them for the site to build correctly.

- My staging website has the title set as “ivy (development)” & the

pages.devbaseURL.

config/production/config.tomlfor production- This config only holds a few settings that we only want on our live site, such as application keys for analytics/comments/etc.

- My production website has the title “ivy (likethevine)”, as well as giscus (comments) settings, and my custom domain baseURL.

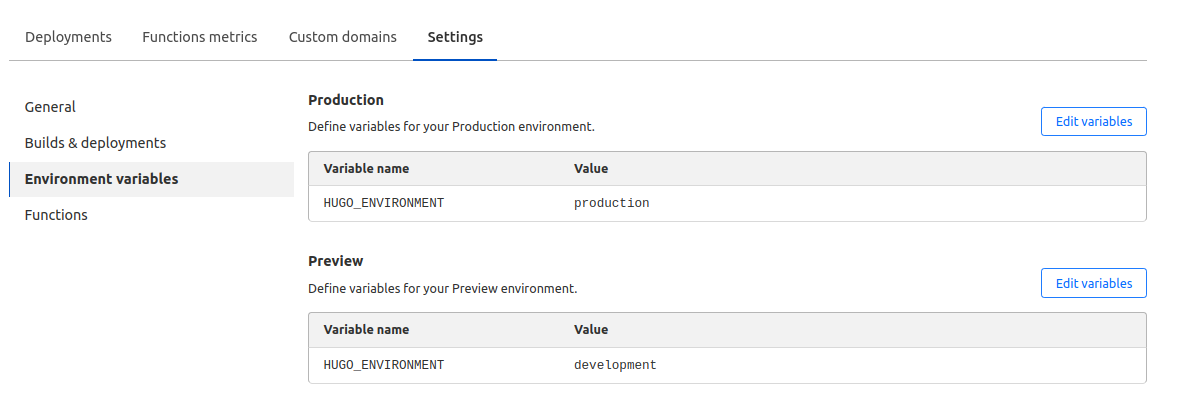

Hugo uses the _default config, but it can apply the production config if passed a flag during deployment. Luckily, since Cloudflare Pages supports Hugo out of the box, we simply need to set a few environment variables in the GUI. Back at the settings for our website, we can define the following flags. These will be passed to the hugo build command when we deploy:

Note: Environment variables are also useful for securing data that absolutely should not be in the main git repository, such as SSH/application keys.

iii. Prevent Disaster with Automatic Checks

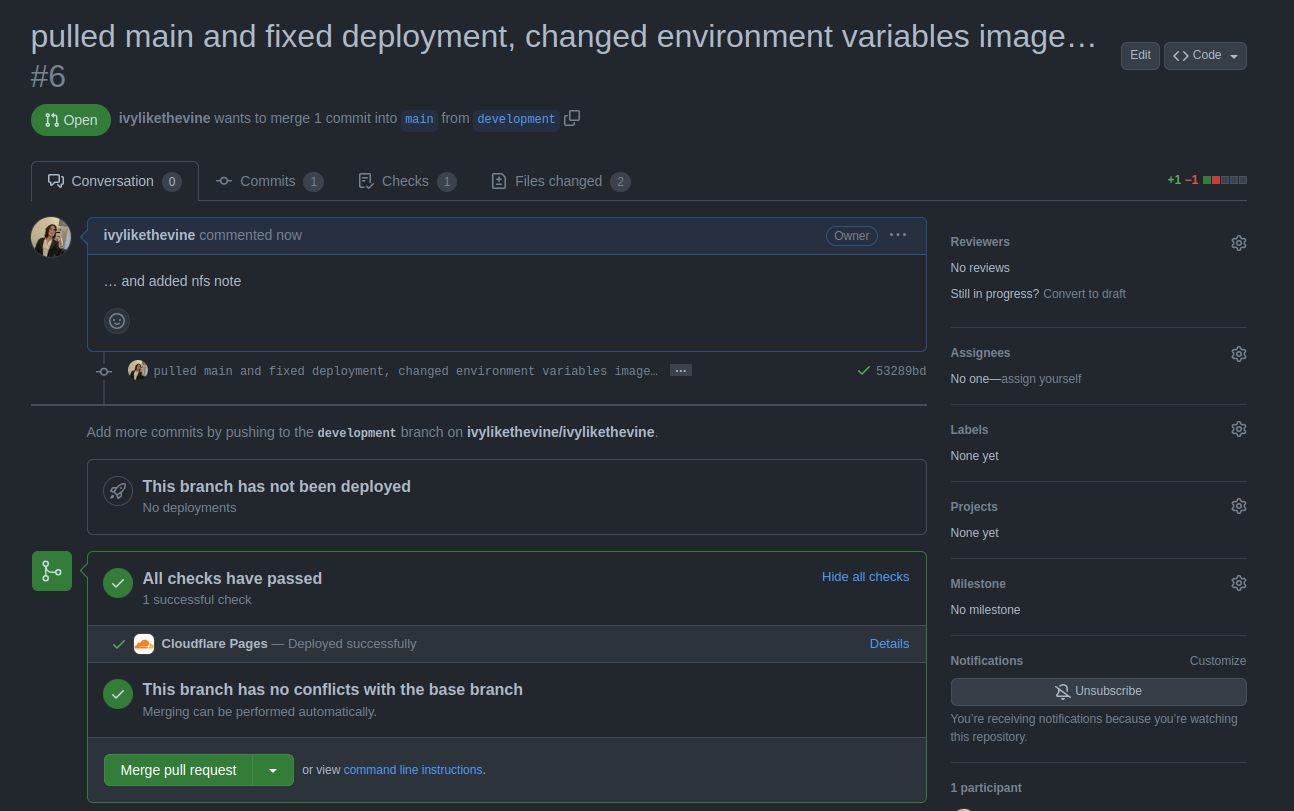

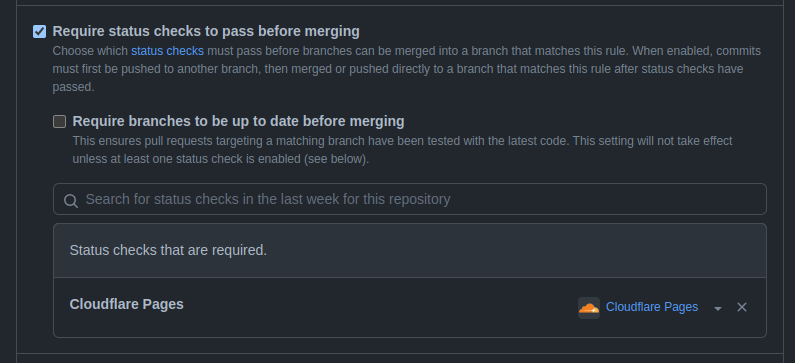

Now that we have our SVM and our automatic deployments, lets talk workflow. Github (and other SVMs) provide many automated checks and systems to prevent the dreaded “new dev destroys prod” disaster. Branch protection rules are super simple and useful. Common rules include preventing direct pushes to main, requiring pull requests to be approved by others before being merged, and tons of more complex versions.

Here are the basic steps to working within a system like this:

- Create a

featureNamebranch off ofdevelopment. - Add a feature/bugfix/etc, modifying as few files as possible.

- Add files & commit at major checkpoints, leaving short but useful commit messages.

- When a feature is ready for evaluation, push to the

featureNamebranch, then open a pull request to mergefeatureNameintodevelopment. - Have the pull request approved & merged by supervisor (or double check manually).

- Test the staging site.

- Deploy to production via pull request from

developmentintomain.

gitGraph commit branch develop checkout develop commit branch featureName checkout featureName commit checkout develop merge featureName checkout main merge develop checkout develop

Reap the Benefits

So with all of that work, what do we really get? Time to revisit those goals:

- Source Version Mangement

- Rule 1: software changes need to be easily assigned, tracked, and checked

- stored in github following git-flow

- Rule 2: environment variables need to be stored safely (important enough to state again)

- dual config files locally as well as environment variables stored in our host

- Rule 1: software changes need to be easily assigned, tracked, and checked

- Deployments

- Rule 1: deploying new versions should be automated via CI/CD and require no human intervention

- most deployments require a simple approve & merge of a pull request (via a Web UI)

- Rule 2: staging site to test versions before production deployment

- staging site automatically deployed from

development

- staging site automatically deployed from

- Rule 1: deploying new versions should be automated via CI/CD and require no human intervention

- Onboarding

- Rule 1: new devs need to be able to download and deploy system within a day2

- with a proper SVM, git flow, and environment configurations, onboarding will be a breeze

- Rule 2: new devs should not be able to break production

- branch protection rules, pull requests, and automated integrations mitigate or prevent most accidental destruction

- Rule 1: new devs need to be able to download and deploy system within a day2

The initial setup takes time, for certain, but now we will gain efficiency almost every single day from now on! Your managers, coworkers, and your future self will thank you, trust me.

Footnotes

-

Slight caveat here, some systems require lots of permissions/database access, which could increase this time, but the repository setup should be quick. ↩︎ ↩︎

-

If you are migrating github -> Cloudflare with a custom domain, I recommend changing the domain registrar to Cloudflare for easier integration. Additionally, if your repo followed the

username.github.ionomenclature, rename it before you deploy to Cloudflare, otherwise your staging site will end up as development.-github-io.pages.dev. ↩︎ -

Stay tuned, I am working on an article about using Cloudflare Zero Trust to safely access self hosted services without network configuration. ↩︎